We publish the report of the workshop we held in Cologne this August at the Rheinmetall Entwaffen camp together with Interventionistische Linke, Inicjatywa Pracownicza, and ∫connessioni Precarie. This workshop was a first step towards a wider assembly on how to organise transnationally within Europe at war. In the wake of a new phase of the movement against war that is shaping the European landscape with a new strenght gained from the involvement in the Global Sumud Flotilla, the massive strikes in Italy, the mass demonstration on the 27th in Berlin, it is clear that we are finally in front of something that the broke the argins and let the antiwar sentiment of the workers, migrants, students, women and queers flow in the streets and in the workplaces as well. “It is more and more important to organize transnationally, and gather strength to have an impact on the local level as well, connecting across barriers and borders.

We cannot remain confined to the national level in our analyses and struggles—especially when it comes to war and militarization. “The war regime connects the distant battlefield with our minds and actions in the here and now” (IL, 2025). War concerns us all—and that is precisely why we can only fight it together: across national borders, beyond campism, warmongering geopolitics, and other regressive approaches that fuel and sustain militarism.

As TSS, we pursue a transnational approach. We work toward a shared understanding of war, its logic, its consequences, and its causes—and we want to oppose this with a transnational politics of peace. Our aim is to connect struggles across national borders and build a transnational organization against war. It should be noted that we sometimes use different terms, such as WWIII or war regime, that often describe similar dynamics.

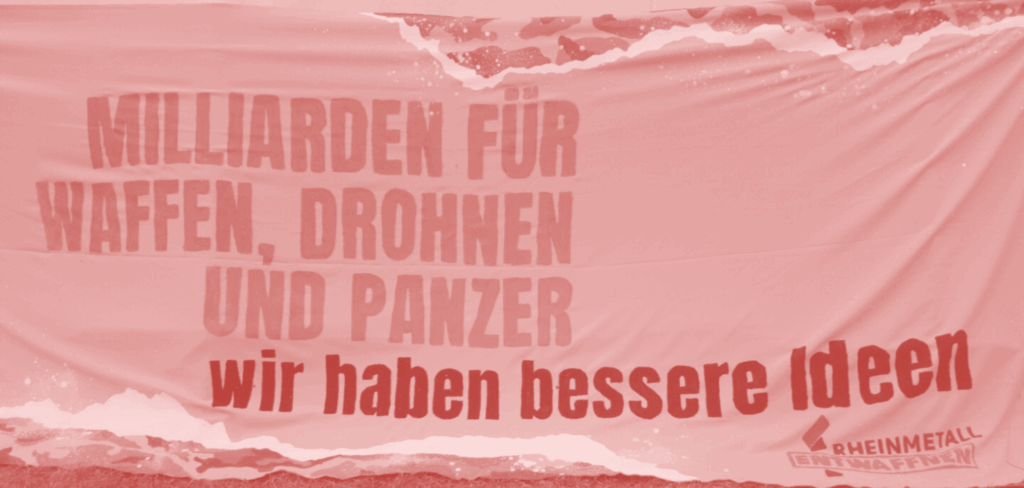

In this spirit, we organized a workshop at this year’s Rheinmetall Disarmament Camp in Cologne at the end of August. Comrades from ∫Connessioni Precarie (Bologna), the Workers’ Initiative (Poland), Agisra e.V. (Cologne), and the Interventionist Left (Germany) discussed with around 200 people who had joined the camp. On the one hand, we discussed how the dynamics of war shape the conditions of our struggles; on the other hand, we considered possibilities and perspectives for transnational organizing against war. Many people attended the workshop and discussed with us how militarization affects different areas of life. The exchange helped to deepen our political understanding and connect comrades and groups—another step toward building a transnational anti-war movement and preparing for a planned Europe-wide anti-war conference in 2026.

Below, we provide an insight into the content and discussions of our workshop.

The workshop opened with a brief yet powerful input from a comrade, who spoke about the appropriation of leftist, feminist, and queer positions by the logic of war. These positions are deeply entangled with the state, NATO, and the military, and their progressive outward appearance is nothing but illusory war propaganda.

“Believe only yourself and your anti-militarist convictions. Because if war comes to your country, you too will have to stop believing in almost everyone.”

- The anarcho-syndicalist trade union Workers Initiative described how, in Poland, the narrative of being a “key state” in the defense against Russia is staged in order to legitimize massive military spending (nearly 5% of GDP) and weapons imports from the USA. For much of the population, the possibility of a Russian attack is seen as a realistic scenario, with Russia itself portrayed as the sole imperialist enemy. The government exploits this fear of war to push through austerity policies, social cutbacks, and military spending. Poland lacks a significant anti-war movement. This absence is rooted in Polish nationalism, which is already aggressively propagated in schools in the form of “national sovereignty,” historically portrayed as threatened by Russia. This fear is instrumentalized for military purposes. Left-wing forces such as the Razem party have abandoned their anti-war positions and now advocate for the expansion of the arms industry. Across Polish society, right-wing narratives are spreading—far from any class analysis of war—that transform initial solidarity with Ukrainian refugees into right-wing agitation. Workers Initiative stands in solidarity with refugees and deserters, actively integrating them into labor struggles. The arms industry in Poland is (still) relatively small, and militarization can be opposed by addressing state military spending and through a general strike in the public sector.

- ∫Connessioni Precarie shed light on the political situation as well as recent developments in social movements and struggles in Italy. Although discussions in Italy about the reintroduction of compulsory military service and the expansion of the army—unlike in Germany—are still unrealistic scenarios, and the NATO 2% GDP target for military spending is barely met, war and militarization are nonetheless present in many areas of society. Looking beyond direct arms spending, it becomes clear that the logic of war has spread throughout society and into people’s minds. War serves to legitimize authoritarian measures, patriarchal and racist violence, and exploitation. A concrete political expression of this in Italy is the so-called Security Decree (*Decreto Sicurezza*). Among other things, it criminalizes social protest and significantly expands repressive police powers.

Furthermore, the expansion of war is evident in the rise of racist discourses surrounding the genocide in Gaza or the war in Ukraine. At the same time, war intensifies the capitalist exploitation of human labor, increasing the precarization of working conditions. Beyond that, living labor is forced to make greater social sacrifices, as in Italy, where much of the state’s social safety net has been completely abolished. The racist narrative portraying migrants as a threat to the country’s internal security is also used to justify deportations and controls. It is clear that Italy’s agreements with Libya or Albania, or the precarization and discrimination of migrants, are not aimed at creating a “fortress Europe” but rather at “controlling the movements of a workforce that keeps on challenging the borders’ regime”. Finally, militarization is reflected in the rise of patriarchal violence and in the widespread normalization of military presence in educational institutions. Social struggles are currently weakened, also because so far geopolitical logic, consisting of territories, diplomacy, and alliances, has taken over our entire political imagination. The aforementioned difficulties are being addressed within the cross-spectrum anti-war initiative RESET, that launched in June the prospect of a European strike against the war and will meet in Bologna on the 11th of October. - The contribution from the Interventionist Left asked: how does the expanding war regime affect our struggles? What experiences have we gathered so far in the context of “Disarming Rheinmetall” (RME)? These and other questions were addressed by the input of the Interventionist Left (iL), giving an overview of the situation in Germany. The debate about a suitable emancipatory practice against war must be conducted in light of the concrete balance of social forces—and this also in comparison with previous cycles of struggle. The increasing authoritarianism and militarization make the development of social struggles and movements significantly more difficult. Our own tactic of civil disobedience, which once relied on a progressive civil society, must be reoriented—for that progressive civil society no longer exists. War and crises have robbed it of the belief in the possibility of emancipatory transformation, and many have been finally and obediently integrated into the machinery of capitalism. Rising repression and state violence continue to narrow the spectrum of opinion, leaving debates often limited to dichotomies and friend-foe logics. RME, and most recently the camp where this workshop took place, is the latest example of these developments: attempts at bans, disproportionate police presence, restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly, and narrow-minded media coverage. The attempt to mobilize the liberal-left civil society for RME failed—the fear of stepping out of the national unity front was too great. The contradiction formulated by RME has become visible, but what emerges from this contradiction when the ability to enforce change is currently lacking?

- From Agisra e.V., an autonomous feminist information and counseling center by and for migrants and all those affected by racism, a comrade emphasized: the escalating global conflicts must not be seen as isolated events but as interconnected systems of violence— along the axes of war, patriarchy, and capitalism. War—closely entwined with colonial and patriarchal oppression—serves to secure global power relations. Women and queer people are particularly affected: through forced care work, economic exploitation, or sexualized violence. But women are not only victims of war; they are also peacemakers and resisters. And because wars do not take place within national borders, the response must be formulated transnationally. This means connecting struggles, sharing strategies and resources, and practicing unwavering solidarity with all those affected by war and its violence. Together, we must dismantle the system of global militarization, whose structures render women and queer people invisible and replaceable. We must show that transnational organizing is not a slogan, but a political practice. And last but not least: “Organize with hope, not just anger. The war machine feeds on despair. But our movements must feed on possibility, on connection, and on the radical imagination of a world without war.”

Discussion and Outlook

The inputs were followed by a discussion around the questions: How does the expanding war regime affect our struggles? And how can we connect and make these transnationally visible? Many of the workshop participants joined the discussion, and without a time limit, we could have gone on forever. Below we share some impressions, inputs, and thoughts from the discussion.

There was agreement that Europe should be addressed as a central actor in the conflict. Against this backdrop, we should examine developments in militarization, which are increasingly enforced not by nationalism but rather by (controlled) citizenship. Those who live precariously and are made dependent on the possession of certain passports are often exploited for war purposes. Refugees, for example, are deliberately recruited in Israel or Russia in exchange for papers. So what does desertion mean when there is no compulsory conscription, but people are nevertheless forced into arms through economic circumstances, for example? The term WWIII is used to point to the changes and new circumstances of wars, and to the need to connect them analytically.

In the way we think about resistance within the logic of war, there is somehow a missing link between lived realities and a moral refusal, an obvious gap, and a declining solidarity movement. The opposition to war cannot be simply a matter of solidarity with those affected by war, but must also address the effects of war on the material conditions of people, extending beyond the war scenarios.

Furthermore, we need to adapt to transnational thinking and action, and to develop a perspective on how to integrate the anti-war agenda into labor struggles. We need to break open the societal consensus on “security” and militarization. We need more places, symbols, and moments like the RME camp, while simultaneously lacking practices that penetrate the spheres of production and reproduction—for it is here that we see the potential to organize struggles and also win them. We must think about how to attack the social causes of war. We must connect militarization and war with our everyday social realities. And even though militarization has changed, we should make use of past experiences in our present struggles.

The workshop was not a conclusive meeting, but an important step on a long road. We were able to share perspectives and understandings, our roles and positions, when speaking of the global working class. By transnational, we mean not a moral but a material connection—together on the path toward a transnational working-class response to war and its causes.

We would like to continue this discussion at the Europe at War Conference 2026; further information will follow.