We publish the interview that Laura (from the TSS Platform) and Hans (from Amazon Workers’ International) conducted with Mac Urata, a labour activist, journalist, and researcher based in Tokyo. He is involved in the Make Amazon Pay campaign in Japan, assisting Amazon drivers in Yokosuka, and providing information about the struggles of Amazon workers around the world to his colleagues in Japan. We met him at the Amazon Workers International meeting in Leipzig in April 2025.

Make Amazon Pay is a global network that brings together activists from different backgrounds (labour, environment, tax justice) who criticise Amazon. The network organises protests around the world on Black Friday. During the AWI meeting in Leipzig, Mac Urata showed us a documentary produced by the Make Amazon Pay Japan Committee. It can also be watched online here: https://vimeo.com/ondemand/amazondspeng. The Committee is available to discuss screenings.

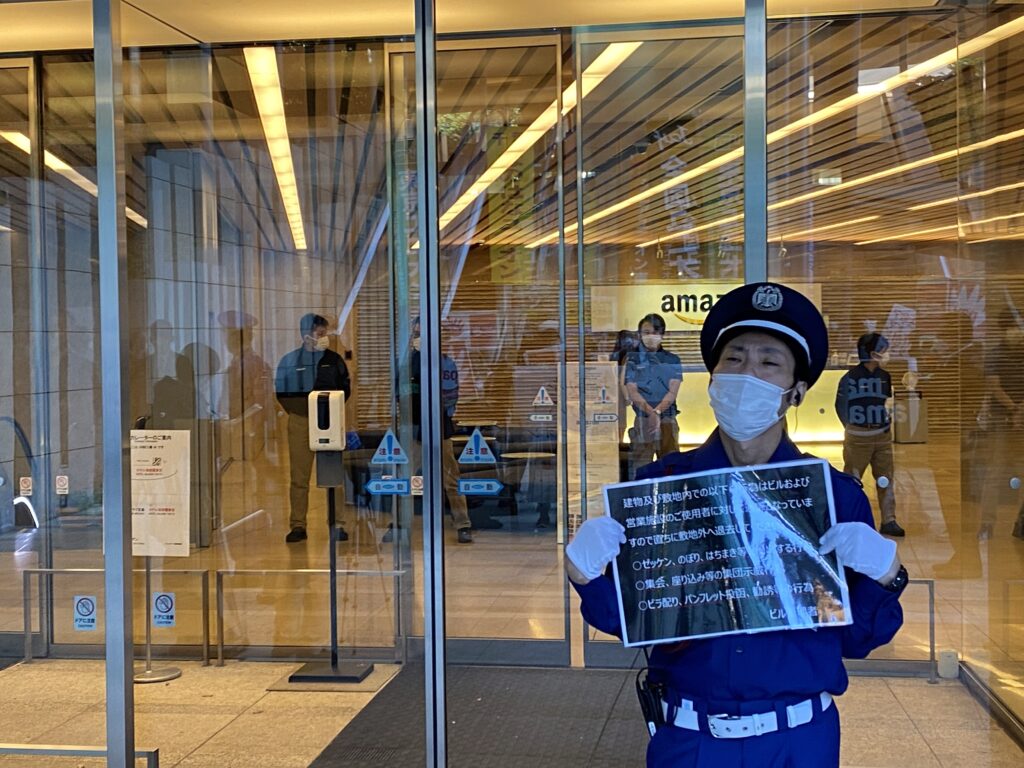

[all Pictures are from the November 2022 Make Amazon Pay protest rally at the Amazon Japan head office in Tokyo. Ph. Mac Urata]

LAURA AND HANS: In Europe, Amazon is by far the biggest online retailer. Amazon is synonymous with online shopping. How would you describe its market position in Japan?

MAC URATA: Amazon is the second biggest player in the Japanese e-commerce sector. The top firm is Rakuten. However, Amazon is not only an e-commerce company. The Japanese competitors do not have a service like AWS (Amazon Web Services, a subsidiary of Amazon, provides on-demand cloud computing platforms and APIs to individuals, companies, and governments), which has won government contracts. E-commerce is becoming more and more popular in Japan, as it is very convenient for consumers. Especially if it is cheaper than what you can get in high street shops, of course, people will prefer online shopping. On the other hand, I do not think many people are aware of the history of tax dodging that Amazon has. They can bring the prices down because they are not properly paying the taxes in many countries.

What has happened so far at Amazon Japan in terms of unionism?

Before 2022, there was no drivers’ union. There was no union in Amazon Japan except for a group of office workers at the Amazon head office in Tokyo. They formed a union because Amazon always cuts off like 10% of the office workers every year in their program.

Amazon applies a PIP (performance improvement plan, here an explaination) for employee assessment, to dismiss a certain number of employees with the lowest performance. Of course, this is very unfair! So, employees at the head office got together to form a union. The union is maintaining its membership, but they do not have a collective bargaining agreement. However, they have enforced better departure packages for the laid-off colleagues.

In our case, the Amazon DSP (Delivery Service Partner) drivers based in Yokosuka, a city located near Tokyo, formed their Union back in June 2022 as The Amazon Delivery Drivers Union Yokosuka Branch. The reason that ignited their protest was that Amazon changed the setting of its algorithm on its app, called Rabbit. Before this change, the DSP drivers used to carry like 80 to 100 parcels per day, but after the change, the number doubled. They ended up delivering like 200 boxes every day, but their pay remained the same. Even though they are treated as independent contractors, the Amazon Rabbit app was instructing them on how to go through their deliveries. And they felt like they were under the instruction of Amazon, but they were categorized only as independent contractors.

The drivers are hired as independent contractors by Amazon subcontractors. They have a fixed rate for the package delivery per shift. Suddenly, Amazon doubled the number of packages per shift. Some drivers in a town called Yokosuka came together and said, “We cannot accept that.” And they went to a law firm in Tokyo, which is well-known for supporting workers. And the lawyers said, “You should form a union in your workplace.” The law firm connected those drivers with a community union, which is called Tokyo Union.

The office workers and the drivers belong to two community unions, which are under the same umbrella organisation called Zenkoku Union. We have an idea that we should have one big Amazon workers’ union in Japan. Let’s see what emerges from this.

What happened after the drivers contacted the Tokyo union?

The Amazon drivers in Yokosuka had meetings with union secretaries. Finally, they formed a union with about thirty drivers. Tokyo Union holds a hotline service from time to time, where any Amazon driver can speak to a lawyer over the phone for free legal advice. The media brings it to the news. Through this hotline campaign, Tokyo Union got in touch with workers in other parts of the country. In Nagasaki, drivers formed a union through this initiative. However, the Amazon subcontractor was replaced. When this transition happened, all the unionised drivers were not offered a new job at the new subcontractor. The union branch in Nagasaki does not exist anymore.

Are all the drivers managed or controlled by the algorithm while they’re driving? How is the algorithm pushing them to work faster? Do you also have webcams inside the trucks, as in the U.S?

The app Rabbit tells the drivers which parcel to deliver first, which one is the next one, the third one, the fourth one, and so on. That is the instruction they give out. But unlike the U.S., there is no webcam in the vehicle. This is because in the U.S., drivers lease vehicles from Amazon. DSP drivers in Japan use their own van. It’s not so easy for Amazon to force you to put a webcam on somebody else’s truck. I don’t think we have that level of surveillance in Japan, but maybe this is coming. Who knows.

You were also explaining at the AWI meeting that, for example, fuel costs a lot to the workers, and they have to pay for it themselves.

The drivers in Yokosuka are paid 19,000 yen (approximately 112 euros) per day, and they have to cover expenses like petrol, insurance, mobile phone bills, etc, which add up to 5,000 yen. So, they are left with 15,000 yen (90 euros) per day. Last year, a group of drivers took the subcontractor to court, demanding the payment of overtime, claiming that they had been misclassified.

Can you tell us more about the concept of ‘community union’ in the Japanese context?

Predominantly, Japanese unions are formed on an enterprise basis, but this union organises differently. The members are organised on the local level. Furthermore, the union supports individual workers with their problems. They help workers with different types of employment contracts, including independent contractors in the last-mile sector. That is unique in Japan1.

What would you say are the main challenges when it comes to organizing together? Is it difficult to find people who can join the union? Are they skeptical, or is it easy to communicate with each other?

As I said, the workplaces for the drivers are often very small, with fewer than ten drivers, and they are always driving. It’s not like a warehouse where you stand next to your colleagues and you have the same time for lunch or coffee break, where you can have a chat with your coworkers. Drivers are not like that. It’s not so easy to communicate between the drivers in the same workplace. So that’s the first challenge.

And they don’t have enough time. That’s the second challenge. And then also, we don’t have a full-time organizer to go out to the workplaces and organize the drivers. Our resources are limited. So that’s the third challenge for us. It is not that DSP drivers don’t care about unions, but I think they don’t know how to access a union to raise their issues. Our Union is still very small, and it is a local union. So, networking is another issue for drivers.

Amazon often fights against unionisation. Can you tell us more about what union work looks like under these conditions?

One task is to increase the membership. The folks in Yokosuka arrange events like open barbecue parties to approach new colleagues. When somebody starts working at the subcontractor, they aim to have conversations to inform them about the benefits of the union.

The union demands a collective bargaining agreement with the subcontractor and Amazon. Of course, both say, “No, you are independent contractors, that is why we cannot bargain collectively.” That said, as the union has been quite active in the workplace, the management of the subcontractor cannot ignore it anymore. From time to time, there are meetings between the union and the management to talk about workplace issues. Furthermore, the union and its lawyers filed several lawsuits against Amazon and its subcontractors.

One court case is about two drivers who were dismissed by an Amazon subcontractor for ”trespassing”. The same thing happened twice in different places. In both cases, the drivers came to the apartment while delivering the packages. They thought that they had entered the public area, but by accident, they stepped onto private property. It was a mistake. However, the resident complained to the subcontractor that somebody had entered his property and left a package. Consequently, the drivers were dismissed. I think it was done in retaliation against the unionised workers.

We have another lawsuit about benefits that Amazon and the subcontractor are denying to the contract workers. The union lawyers argue that the drivers are misclassified and that the firm owes them overtime pay. We also won two cases of compensation for workplace accidents. In Japan, you are only awarded this compensation if you are an employee. There are many workplace accidents because the drivers are always in a rush.

How did Amazon respond to some of the past workers’ mobilization? Was there a successful strike during these three years, or a successful come-out?

Amazon has stated that these drivers are independent contractors and they don’t have any right to bargain collectively. “We don’t employ them. It’s the subcontractors. So we don’t negotiate with them”. And that has been their position all the way through. There was a strike in a city called Nagasaki a couple of years ago. There was a change in subcontractors, and the new company did not recruit union members. But again, Amazon said they are not in a position to meet with the union to resolve this matter. They have been very clear about how they see the Amazon drivers. And since 2022, on Black Friday, on the Make Amazon Pay Campaign Day, a group of drivers, unionists, lawyers, NGO people go to the Amazon head office in Tokyo for a protest rally, and we always have a letter with a set of our demands. But in 2022, they hired security guards, and they didn’t even let us go to the receptionist’s desk to leave the letter to Amazon. We had to leave this letter on the floor of the reception.

It’s a long and hard struggle. They are against the union and the demands of the union. Last year, the representative of our group did manage to leave our letter for Amazon at their reception, but of course, they didn’t respond.

So there are many independent contractors in the union, not employed directly by Amazon. How many subcontractor companies are there?

Yes, exactly, these independent contractors are the members of the union. They work for a subcontractor of Amazon. They are not hired by Amazon. They work 12 hours a day and five days a week. And their salary is fixed. So, no matter how many parcels you carry per day, what you get is the same. Sometimes it is impossible to complete their task without some overtime, but there is no overtime payment for the extra work. And in the past, there were cases when Amazon subcontractor managers said, “Switch your ID”, to work more hours. The IDs were for some other drivers who were not on duty that day. Or some drivers who had already left the company.

I think there are about a dozen First Tier subcontractors for Amazon Japan. These firms then use small-sized second-tier subcontractors. How many? Perhaps a few thousand firms? They often have fewer than 10 drivers. Back in 2019, a larger First Tier subcontractor said they needed 10,000 drivers.

We talked a lot about the institutional power resources of the union, which rely on labour law. However, the strongest power resource of the working class is the strike. The right to strike differs a lot from country to country. What is the situation in Japan?

In Japan, employees have the right to organise and to participate in strike actions. Private sector workers in essential services have to notify their employer within a certain number of days. Of course, you also have to ballot your members at your workplace and get the support of the majority. Public sector workers are denied their right to strike. It is a case that the ILO has consistently told the Japanese government to correct. The Amazon workers are independent contractors. I do not think that the same laws would apply. Technically, the drivers can decide not to work on a certain day, as they are independent contractors. You can call it a strike or sick leave. However, the management can retaliate and punish the workers who went on a strike by claiming that they broke the contract agreement. They can be dismissed from their services. So, the drivers are not doing that for now because the consequences may not be so good for them.

So, in Japan, it should be illegal to work all those hours. Is there some law that prohibits working more than a certain number of hours?

In principle, truck drivers’ working hours are 8 hours per day and 40 hours per week with some flexibility. And Amazon Japan has a policy that your maximum working hours are 12 hours a day and 5 days a week. So, subcontractors must show Amazon that they are complying with the Amazon policy. That was why they used fake IDs to manipulate the record. They stopped this practice after we exposed it to the media.

Campaigns like Make Amazon Pay try to mobilise societal support. How does Japanese society react to the labour conflict at Amazon and your public campaigns?

When the union was formed, it was quite a big story for the press. Some mainstream media reported on the Amazon drivers in Yokosuka. However, public awareness is low on the exploitation of these workers. That is one of the reasons why we have produced this documentary film. We wanted to raise public awareness about the drivers’ working conditions: “You are in a convenient situation because your package arrives on the same day or the next day at your doorstep. But how much do you know about the problems of the drivers who handle your delivery?” That is the campaign message through that documentary film.

Can you report to us what you did concretely on the Make Amazon Pay protests?

For the last three years, we have visited the Amazon head office in Tokyo with a delegation of unionists, lawyers, NGOS to submit our demand that Amazon has to bargain collectively with the union. Of course, the management did not accept such correspondence from us. We walked straight to the reception and, of course, they did not let us in. So, we had our rally with shouting and slogans for thirty minutes in the entrance hall to make sure that Amazon heard our demands. Fridays For Future (FFF) Japan also went to the Amazon head office on the same day at a different time, and they submitted their demands as well. Amazon also did not meet with the FFF activists.

Most workers who take part in the Amazon Workers International meeting work in the big warehouses of Amazon, which are called fulfilment centres. In Germany, those are the main focus of the union’s strategy. What about the situation of the warehouse workers in Japan? What are the obstacles to organizing them?

Our union is identifying individuals who could take up organizing efforts in fulfilment centres. We already have some collaborators. They told us that the workers have short-term contracts. So the mindset of warehouse workers is often “why should you complain about your working conditions when you are out of this place anyway in the next few months?” If you complain, you might get dismissed earlier than the expiry date in your contract. There is both strong fear and a strong sense of apathy, I think, among the workers.

There is also another aspect. The working conditions in Japan may not be as harsh as what you hear in other countries. It would appear that in the UK, for example, there are many more workplace incidents than in Japan. One reason could be that most workers are Japanese citizens, as Japan has more restrictive migration laws than other countries. In other words, Amazon cannot find many migrants as disposable.

What is the workforce composition? Are there migrant workers employed? And if there are some, where do they come from?

No, there is no migrant driver in the Yokosuka union branch. However, I once met a group of Japanese Brazilian Amazon Flex drivers. It is not that we don’t have any migrant workers. But many of these Japanese Brazilian drivers are born or raised in Japan. There’s no issue with the language, for example, or the residence permit. Unlike Europe or the U.S., it’s not like migrant workers coming to your country looking for a job and then finding a job at Amazon. I also think the number of migrant workers is small in Japan if you compare that with the U.S. or Europe. There are migrant workers in Amazon warehouses. I guess that they come from Vietnam, China, and Southeast Asian countries.

Yes, in Europe, the share of migrant workers at Amazon, especially in the last-mile sector, is very high. What motivates Japanese workers to start working at Amazon under the conditions you have mentioned?

You have the opportunity to be your own boss as an independent contractor. It is attractive that you are not told what to do by your managers at work face-to-face. However, that is only your inception before you start driving. As a driver, you are controlled by Amazon’s Rabbit app all the time and are tasked to deliver a large volume of cargo. I think such a gap produces anger for the workers. They say, “I thought I was an independent contractor. I thought management would assess me with my performance, but no, they do not make any assessment or evaluation of my job performance.” That leads to big frustration.

It is nice to meet you here, but we agree that it would also be good if Japanese Amazon workers came. What are the obstacles to bringing workers from Japan to international workers’ meetings in Europe or North America?

The language barrier is the biggest obstacle. Japanese people learn it at school, but whether they become fluent is another question. Another problem is whether the rank-and-file workers can take the time off to travel long distances. It is a one-week trip. It is a challenge for the drivers to take so many days off when they have no paid annual leave. I think the management at the subcontractors takes it for granted that these workers work regularly for them. It is not so common for Japanese to go on a one-week holiday under such conditions. Of course, funding is another issue. I think they will think twice about the costs of travel and accommodation.

It is important that they learn how the workers in other countries are organizing their unions, which campaigns they are initiating… We can learn about their tactics and use them here because it is the same employer that uses the same labour policies. For example, Italian drivers are not independent contractors. How did they achieve that?

Also, we can expose local issues to a global audience through unions. One fine example is the health and safety campaign in India during the heatwave last year. I think that Amazon is sensitive to public opinion.

Imagine that workers from all over the world show solidarity if there are big issues between Amazon Japan and its workers. That would put some pressure on the management. How can consumers and shareholders be on the same page with us?

The Amazon drivers and office workers in Japan are part of one big family of Amazon workers internationally, and they are not alone in their struggle against Amazon Japan, but they are supported, they are assisted at least morally by the colleagues from other countries in the Amazon unions. It is a big motivation for the Amazon workers in Japan in their struggles.

- Community unionism in Japan can be compared with the workers’ center approach in the USA, but it is still Japan-specific. It is a new model of unionism which reflects the changes in post-Fordist labour organisation, which can be observed all over the world. For more information, see Royle, T. & Urano, E. 2012. A new form of union organizing in Japan? Community unions and the case of the McDonald’s ‘McUnion’ in Work, Employment and Society 26 (4), 606 – 622.

↩︎