by alternator

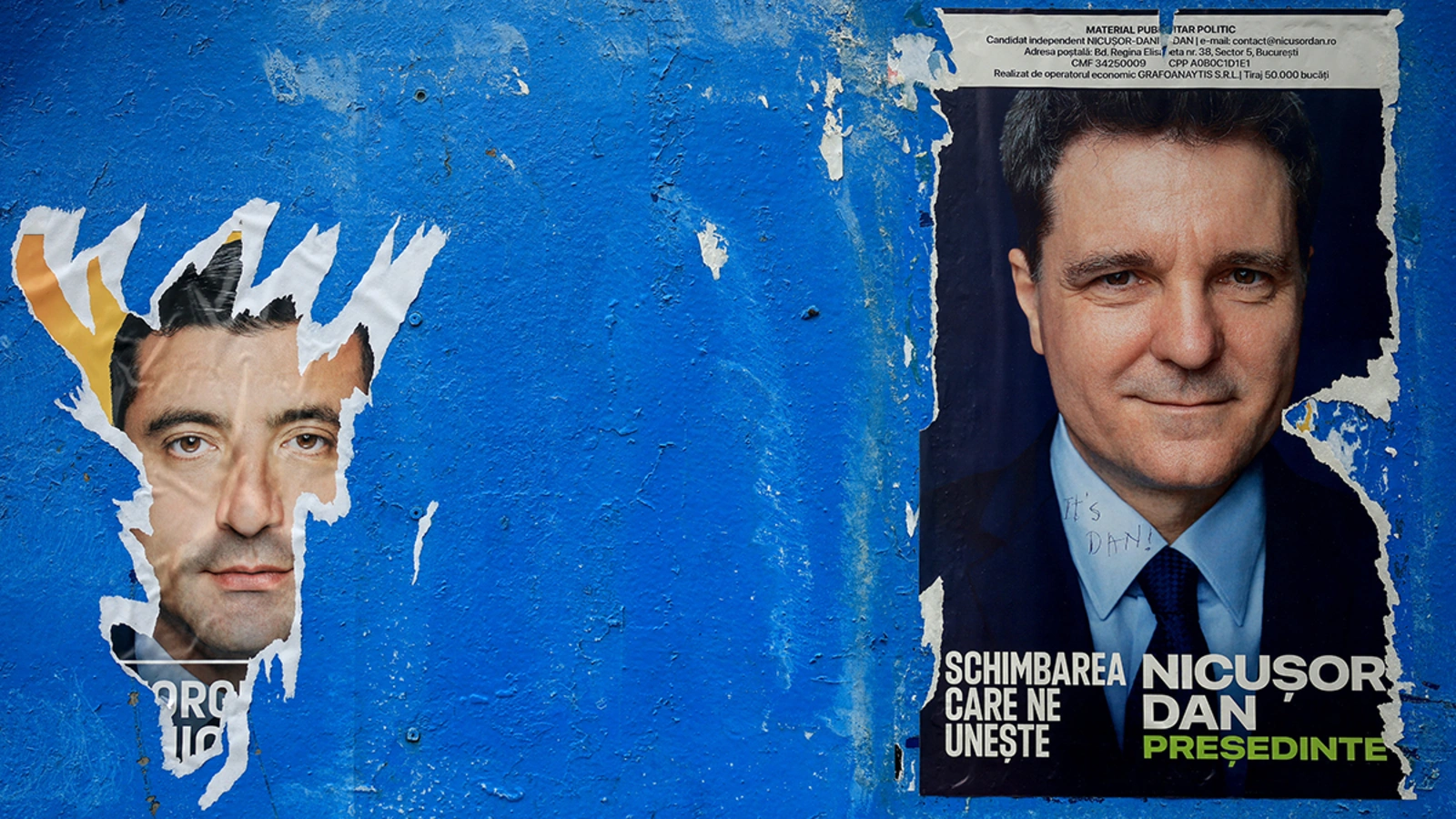

This is the first part of an article by the Romanian collective Alternator about the last presidential elections in Romania. On 18 May, the pro-European candidate Nicuşor Dan defeated his fascist, pro-Russian, and Trumpist competitor, Georgie Simion. Despite their different geopolitical stances, Dan’s victory represents just another face of European militarism: a strong role of NATO, unconditional support for war, increased military spending, and more austerity measures. The elections revealed the contradictions arising from nearly twenty years of privatisation and neoliberal policies, which were legitimised by a “Europeanist narrative” that demanded sacrifices in exchange for the promise of future prosperity. As the authors argue, this Western promise of integration and progress has now failed and paved the way for nationalist and fascist propaganda.

The Romanian elections show the unacceptable nature of the dire alternative between pro-European neoliberal policies and fascist nationalism, both of which reinforce each other. Europe at war is now bringing to the surface all the contradictions of the integration of Eastern European countries, an integration conducted on neoliberal principles that reinforced capitalist exploitation and racist, patriarchal and geographical divisions and inequalities. In this Third World War, militarism and economic austerity are the two manifestations of the ongoing war for the control of social conflict and the imposition of social peace. We must reject these imposed alternatives and find new ways to struggle transnationally for our part, against violence and exploitation.

***

December 8, 2024, Yas Island, Abu Dhabi Grand Prix. Among the spectators at the final race of the Formula 1 championship is Gabriel Vlase, director of the SIE (Foreign Intelligence Service), one of Romania’s key institutions under the Supreme Council of National Defence.

At the same time, the country was experiencing one of the most controversial moments in its recent history. On December 6, the Constitutional Court annulled the results of the first round of the presidential elections held two weeks prior, in which Călin Georgescu, a previously unknown candidate, had won decisively, surprising the main state institutions (including the SIE). The exceptional measure was justified by alleged foreign interference in the electoral process, hinting at Russian involvement. Consequently, Călin Georgescu was excluded from the subsequent election round, held in May this year. His sovereignist and fascist positions were then championed by George Simion, leader of the country’s main anti-system party (AUR).

Defeated in the subsequent elections on May 18, George Simion contested the results by filing a similar appeal to that made by pro-European forces months earlier, this time alleging interference by France and Moldova in the elections. The Constitutional Court deemed the appeal unfounded and dismissed it. The evidence provided in both cases by the Constitutional Court and other state institutions (including the SIE) proved inconclusive. Despite this comprehensive failure of state bodies, so-called pro-democratic sympathizers praised the decisions in both cases, viewing them as triumphs of democracy. This brief summary of the last two elections highlights the pressure faced by state institutions in supporting, with their apparent impartiality, one candidate over another. The state bodies defended the system but now face the most severe credibility crisis since the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the fascism currently forced to retreat may exploit this institutional fragility in the near future.

In light of this, the logical question arises: what status quo has the system defended? Essentially: who won the elections?

Another 5 Years of Swan Song, Scraping the Bottom of the Barrel

“We will support some expenses that, in an ideal world, would be absurd, but we will bear these costs precisely to discourage a war.”

— Nicuşor Dan’s stance on military spending

“I sincerely appreciate your message and greatly value the deep historical friendship that binds Romania to Israel. I assure you of my commitment to strengthening the relations between our nations.”

— Nicuşor Dan’s response to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu

With Nicuşor Dan, simply another face of European militarism has won. Both candidates advocated for a strong role of NATO, increased military spending, and production. On one side, the pro-European Dan envisioned a Romania integrated into a European defense system unwilling to sacrifice the Ukrainian front and promoting a hardline stance against Russia. On the other, the fascist candidate George Simion supported a line more aligned with U.S. rhetoric, willing to sacrifice the Ukrainian front to maintain an open dialogue with Russia. Last week’s electoral clash once again highlighted the crisis within the NATO bloc, divided between a pro-European line and a MAGA line tied to U.S. geopolitics. Despite these differences, neither position escapes the militarizing mantra: both candidates wielded the rhetoric of peace but were ready for war in the name of peace.

Both candidates, therefore, support militarism and have also promoted impactful austerity policies economically. Where Nicuşor Dan’s rhetoric radically diverged was in his unwavering defense of “European values” and political-economic alignment with Western Europe. However, the last-minute victory of Europeanism should not be interpreted as “a new hope” (in Romania, in recent decades, “new hopes” have always translated into neoliberal waves) but rather as the swan song of a faltering system (Romania’s) and a depleted narrative now reduced to an empty shell (Europeanism).

While Dan’s discourse merely rekindles the dying embers of a languishing Europeanism, his political line does not resolve (nor can or wants to resolve) the contradictions that gave rise to the Georgescu phenomenon. The accumulated anger, so effectively harnessed by the right in recent years, has not vanished like snow in the sun after the last electoral round.

It is, therefore, worthwhile to examine the contradictions fueling fascism, many of which originate within the European narrative itself.

Europe Between Broken Promises and Wounded Nationalism

While it’s true that Romania, like other Eastern European nations, was shaped by over forty years of socialism, it’s also true that society has experienced 18 years within the European Union and a process of integration initiated in the 1990s.

We can thus speak of a “Europeanist narrative” that, for over thirty years, has portrayed the West as the horizon to aspire to, the place of prosperity and civilization whose ideals (social and economic) are to be embraced uncritically.

After the fall of Ceaușescu, the path toward the West demanded a high price. Entire infrastructures and industrial sectors were dismantled within a few years. Anti-corruption policies promoted by the International Monetary Fund and the European Union (as necessary steps for integration) justified market liberalization and the privatization of numerous welfare sectors. In short, the economy and society were subjected to powerful neoliberal waves that exacerbated extreme precariousness for a significant portion of the population.

These sacrifices were legitimized by the promise of prosperity linked to European accession. Over the years, various metaphors have been used to describe the integration process. Integration as “the coming home of the lost children into the fold of the family,” where Eastern countries were depicted as children expected to become “mature.” Integration as a “journey,” a departing train that Balkan nations, being late, must hurry to catch while there’s still time.

In the Romanian context, national pride, once exalted to the extreme during Ceaușescu’s years, suddenly became obsolete and anachronistic—an identity tied to the communist nightmare, to be discarded in favor of Western ideals deemed universally superior. On one side was the so-called “Balkan heritage”—uncivilized, corrupt, and barbaric—and on the other, the possibility of “becoming the West.” Notably, the slogan still repeated ad nauseam today: “vreau O Țară ca Afară” (“I want a country like abroad” – meaning Western countries).

In this sense, Romania’s entry into NATO in 2004 and the EU in 2007 was seen as the culmination of a long-pursued dream.

This article does not aim to assess to what extent the past decades have constituted an improvement or deterioration, nor is it useful to indulge in sterile nostalgia. The point is that this Europeanist narrative has failed, and the promise it conveyed has been broken.

While Western Europe, since the 1990s, has benefited from new open and vulnerable markets, raw materials, and cheap labor, after years of integration, Romania remains a “periphery,” a second-hand country within the Union. To justify the failure (or, for optimists, the mere delay) of the integration process, the concept of corruption has always been pulled out of the hat—a term so overused that it has lost its meaning.

Europe – Spatial Stratification and Corruption

Since the fall (or rather, the defeat) of Ceaușescu’s regime in 1989, corruption has always been used as an ideological weapon to introduce privatization policies and dismantle remnants of the socialist state. Even today, during the presidential campaign, Nicuşor Dan brandished the concept of fighting “corruption.” His goal, though presented in terms of efficiency and transparency, is to impose an increasingly corporate style of governance. The far-right of Simion essentially wants the same thing: austerity in a state guided by capital interests.

The real novelty lies in how the far-right has reinterpreted the concept of “corruption” over the years. It is described as a foreign disease, injected by a “contaminated Europe” into the body and soul of the Romanian nation. Following this line, the far-right draws from the vast ideological repertoire of 1930s Romanian fascism, which similarly spoke of the need to purify the nation from an impure threat—then, the scapegoat was “Judaism.”

Simion attacks the ruling class, which he calls “the system,” profiting from the economic structure imposed by Brussels. Mocking the servile attitude of Romanian politicians, he argues that only a return to original values—Orthodoxy, patriarchal values, and nationalism—can bring about change.

The neoliberal nature of the European project, which has allowed the accumulation of power and wealth in narrow circles and legitimizes Europe’s functioning as a stratified space, fuels the far-right discourse.

That in Romania this response is articulated around corruption is a matter of political tactics and concerns the almost sacred character the term has acquired since its introduction in Eastern Europe by the IMF and the World Bank. Economic and power inequalities inherent in capital and Europe (call them “corruption” if you like) must first be attacked politically: legalistic, culturalist, or moralist approaches are mere smokescreens. Secondly, they must be understood as international problems, not local or specific to a “corrupt nation.” Failing to grasp these points means continuing to give strength to two equally non-existent and toxic mirages: that of an ideal and perfect West (according to neoliberal logic) or that of an ideal and perfect past to return to (according to fascism).

Summing Up

The mirage of the West is fading in Romania, and any Nicuşor Dan must now confront this unfulfilled promise. An economic crisis is underway, decimating the middle class, compounded by austerity measures and the risk of an imminent recession. Added to this is the fear of a war, perceived as linked to NATO and European interests—a war not seen as beneficial to Romania but one for which Romania will pay the price, being in a border zone.

Many Romanians are aware they’ve been living for decades in the waiting room of the West. This liminal condition is increasingly perceived not as transitory but as structural to the European order.

In Romania, much of the opposition to fascism has strived to reiterate how beneficial European integration has been and how many protections NATO can offer. The problem is that we are in the midst of a political, economic, and social crisis, and we know well that when the house is on fire, urging someone not to complain about present problems because they don’t realize how much better things are compared to the past is a poor strategy.

In a nutshell, as is the case throughout Europe, the right fills the large gaps left by the left. What is perhaps unique about the right in Romania, compared to Western Europe, is that it has been able to flourish in the blind spots left by this failed narrative and to capitalize on an anti-colonial or at least critical discourse toward Europe—something the left has unfortunately failed to make its own so far.

Between Scylla and Charybdis

We find ourselves crushed between two forces: neoliberalism, on one side, and fascism, on the other. The most disturbing aspect is that, with due differences, a scenario similar to the interwar period seems to be repeating itself—when the state institutions of an increasingly repressive and discredited regime were corroded and ultimately defeated by the fascist movement, which rose to power by denouncing the corruption of a system subservient to foreign interests and calling for a return to an idealized past.

At a European level, for several months, Romania was at the center of media attention: a distant, wild, and exotic frontier where, seemingly out of nowhere, a bizarre pro-Russian fascist emerged from the depths of Twitter, riding a white horse and wearing traditional clothes, nearly winning the presidential elections by arguing that water bottled in plastic blocks the transmission of vibrations and frequencies.

The victory of Nicușor Dan thus calmed fears by securing the only element necessary and sufficient to reassure the Eurozone: Romania’s alignment with EU positions. The system unexpectedly withstood a major blow and earned a few more years of swan song, but the anger remains, along with the contradictions that fuel it. Romania will once again vanish from the radar of “relevant Europe,” accumulating entropy in the calm before the next storm.

Being able to stick one’s head in the sand for a few more years, denying the existence of fascism until the next election cycle: such naivety may be affordable for a liberal, but not for us.

War will come, and it will have fascism as a precondition—in Romania as in Italy and the rest of Europe. Any attempt at internationalism and militant anti-militarism must pass through a decolonization and deconstruction of the European narrative and its spatial conception.

Many local and context-specific factors have contributed to this situation in Romania: the reactionary stance of the Orthodox Church, the ongoing apologism for the Legionary movement (the fascist movement in Romania in the 30’s and 40’s, just to name a few. However, alongside these are broader European and international issues—collective ones—and it is on these that we have chosen to focus.

This text aims to be a tool for understanding the contradictions of the current European moment—contradictions that demand a response that is truly international and rooted in solidarity. The Romanian context is only one aspect of a broader European crisis and must not be passively regarded as a crisis unfolding in a place “other” than our own. The risk is to fall into exoticism and to reproduce the very same narrative that has, until now, confined Eastern Europe to the role of an imperfect other in contrast to a triumphant West.